Introduction

South Africa was ruled by a lawful segregation known as apartheid for almost half a century. A hierarchy was put in place to discriminate against black and coloured, or mixed race, members of society. A history of racial oppression and condemnation has led many to question whether America is implicated in an apartheid of our own. (Pela) I am particularly interested in the way South African apartheid theater is produced on a New York City stage. Stylistic and directorial decisions can bridge the gap between apartheid South Africa and present day America by calling upon cultural commonalities, especially those related to race. Because the topic of transnational theater and race relations are so dauntingly broad, I will be analyzing this topic through the lens of my personal experience with it. Namely, I will use The Signature Theater’s production of Boesman and Lena that I attended as a focal point by which I will analyze this topic.

Boesman and Lena

Athol Fugard’s play Boesman and Lena follows a coloured couple in the mudflats of South Africa. The play revolves around the pair’s personal struggles with dislocation and consequential domestic violence. The Signature Theater’s production of the play in 2019 did well to keep its roots in South Africa, while still catering to its audience in NYC.

Set Design

Staging an apartheid play in NYC means balancing the text’s original setting against the possibility of relocating the characters entirely. Though a play’s South African origin might be crucial to the story, a designer could just as well decide to move the plot to America, making a blatant commentary on American race relations. If a play about lawful segregation could work so seamlessly in an American backdrop, the audience has no choice but to draw connections to oppression of black Americans. Boesman and Lena at The Signature Theater struck this balance. The set was barren and muddy, indicating South African mudflats. It was ambiguous enough, though, that one could imagine these characters elsewhere. As I watched the show in NYC, talk of racism and obeying the white man was all too legible to my American sensibilities. As Max McGuinness wrote in his analysis of the play, “Fugard’s portrait of despair and dispossession has immediate contemporary resonance in a city where homelessness has soared in the past decade and in a nation consumed with rows about migration.” (McGuinness)

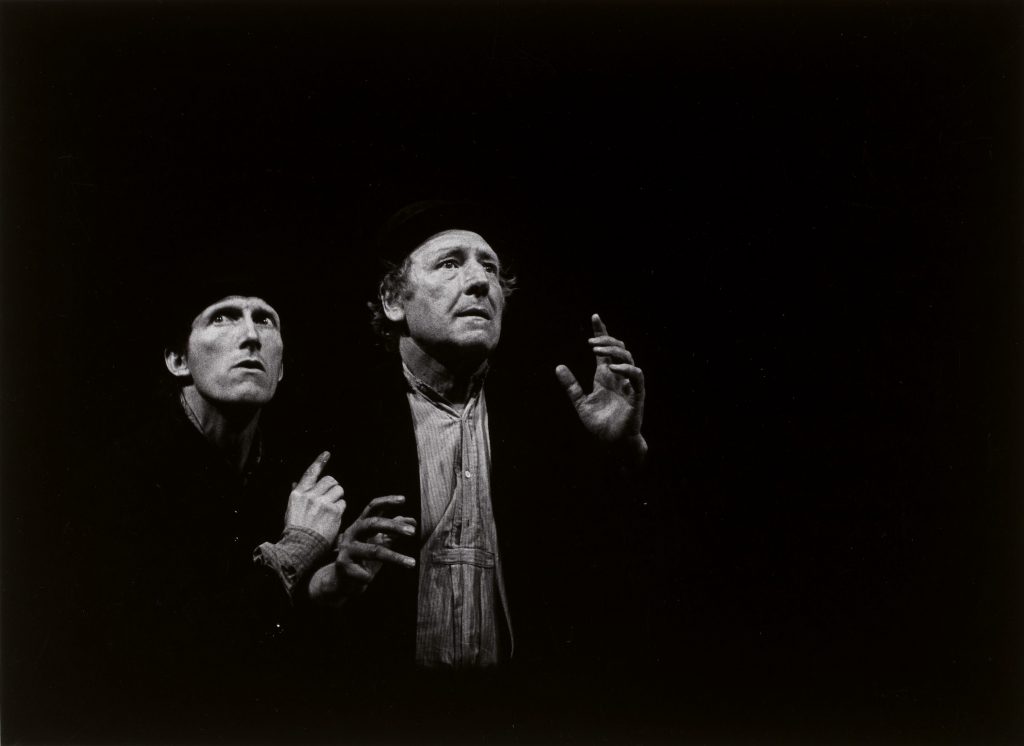

McGuinness goes on to compare Fugard’s play with Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, and he is not the only author to notice this parallel. In his review in the New York Times, Jesse Green writes, “… where Mr. Fugard calls for a bare stage, the designer Susan Hilferty has allowed a single bent tree to grow, which by now is a Beckett bat-signal pointing to “Waiting for Godot.” (Green) To call on imagery of one of the most influential western dramas of modernity is to bolster Boesman and Lena’s potential as a global text, able to shapeshift and speak to audiences around the world.

Dialect

The Signature’s production of Boesman and Lena made a concrete choice that anchored the play in its South African context. The two main characters spoke a South African dialect, while the third character spoke Afrikaans. The director could have chosen to really blur the lines between South Africa and America by having the characters use American accents or by translating the Afrikaans. The languages were kept according to the original context, though, and thus made the audience aware that the characters on stage were living far from where we sat. This element is crucial to remind the audience that despite presenting possibly American themes, this play was written in a specific historical and political context that is not to be ignored.

Costume Design

The ambiguity of the somewhat barren set design was echoed in this production’s choice of costumes. There is nothing inherently “South African” about the appearance of the three characters. They could, again, just as well be living on the streets of New York City. A touch of South Africa is subtly woven into the costume design, though, as Boesman’s jacket bears the colors of the South African flag. This stylistic touch worked to the same effect as the dialect, anchoring the performance to its national roots.

The Conversation at Large

Boesman and Lena at the Signature Theater is an excellent example of the analysis one can take from a culturally rooted play put into performance on the global stage. While it is fruitful to compare the race relations of apartheid South Africa to present day America, it is just as crucial to recognize the specific historical context of apartheid in order not to diminish its significance and devastating consequences. The conversation of global themes of power and oppression should occur where universal generalizations meet contextual specificity. Only then does the theatrical art form reach its full potential.

Works Cited

Green, Jesse. “Review: After Apartheid, Who Are ‘Boesman and Lena’?” The New York Times, 26 Feb. 2019.

Marcus, Joan. Zainab Jah and Sahr Ngaujah . 2019.

McGuinness, Max. “Boesman and Lena — a Racially Charged Waiting for Godot Set in Apartheid South Africa.” ProQuest, 27 Feb. 2019.

Michaud, Fernand. En Attendant Godot, Festival D’Avignon. 1978.

Pela, B. “Apartheid in America.” South African History Online, 1962.