Overview

Long before cameras and videos, the recorded “footage” of ancient plays was limited to ceramic creations such as decorated vases and intricate sculptures. This page will explore the capturing of Greek theatrical performances on such forms of pottery as well as the process of painting a narrative scene.

The Vase

Throughout the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., Athenians explored various techniques to create decorated fine pottery for everyday use and preserving various social or political phenomenon. Fig 1. showcases the process and methods employed to create Athenian pottery, specifically a vase. The function of an object would dictate its construction though all pieces were thrown on a pottery wheel (Department of Greek and Roman Art, 2002). Larger objects would be built in separate components and later assembled with slip (liquidy clay) into their final form. More intricate pieces would later be painted and embellished to showcase an individual’s identity (if the object were to be placed in a tomb), a social scene (if on public display) or a specific theatrical tradition, such as a procession, performance or festival (Green, 1999).

Elements of Performance

The Audience

One major element to consider when examining vase paintings is the ways in which audience members and artists imagined performance traditions. Spectators would go to the theater to experience a cathartic spectacle, while also upholding their civil duties as citizens of Greece. What was specifically enchanting about the acting? What costumes stuck out? As minimal texts have survived on the specifics of theatrical performances, we must look to other mediums to uncover what it was like to be a part of an Athenian audience (Green, 1999).

Myth and Processional Ritual

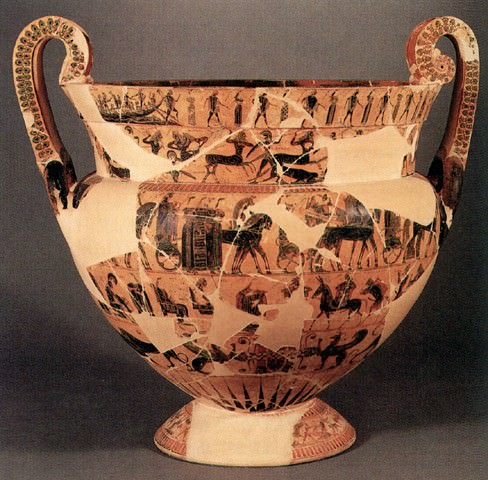

Besides theatrical traditions such as play performances or dramatic poetry presentations, processional rituals, imbued with mythology contributed to the religious and social spectacle scene in Ancient Greece. Ironically, such visual representations of mythical stories diverge from written accounts (Hedreen, 2004), suggesting that vase-paintings focused on elements of artistry, sometimes even altering the known narrative of specific anecdotes or traditions. One specific story, ‘the return of Hephaistos to Olympos,’ often maintains the important theme of power imbalance and dispute among the gods. Ancient literary accounts showcase the disruption of the Olympion hierarchy and its rebalancing through the acceptance of Hephaistos and Dionysos.

And while the original essence of story the comes through in pottery pieces such as the “François Vase” (fig. 2) from c. 570 B.C., the central focus is taken away from the protagonists and, instead, placed on nymphs and sirens accompanying Dionysos. The collective image displays a procession of drunk, whimsical and lacking in self-control spiritual beings that seems to take away from the deeper lesson or message of the story. In this way, the visual representations of this myth relate more to a specific form of Dionysiac processional ritual than the story itself. The inclusion of musical instruments as well as the singing nymphs may represent the euphonic atmosphere of processions. The presence of a large crowd, a great deal of alcohol consumption and exposure of the phallus resonate with celebrations of Dionysos such as processions in Athens during the City Dionysia. By incorporating aspects of spectacle that derive from religious life into vase-paintings, artists were able to maintain the fundamental themes of the myth while also conveying what pious traditions looked like in the city of Athens (Hedreen, 2004).

The Theater and Religion

One of the biggest theatrical events in Ancient Athens was the City Dionysia, or the festival of ample wine-consumption and competition of plays. Playwrights would work tirelessly on dithyrambs, tragedies or comedies in order to win the ultimate prize and a great deal of prestige. While the festival itself was filled with merriment and joy, it maintained a serious religious undertone as the entire ordeal was dedicated to the god Dionysus. Since the sixth century B.C., The Theatre of Dionysus has been used for such theatrical celebrations as the Dionysia. The Greek emphasis on religion burrowed itself into society, even after the Empire’s decline. In the early fifth century AD, an additional bema (podium for an orator) infused roman reliefs (fig. 3) into the front of the stage (Sturgeon, 1977). Though the origins of this addition are not entirely known—it may have been moved from an older stage building or an altar from the sanctuary of Dionysus—it did come from a location close to the theater. The sponsor, Phaidros, showcases his knowledge of poetry and philosophy with his donation while also donning a pious hat as he maintains the original function of the theater’s devotion to Dionysus (Burkhardt, 2016). The relief sculptures act as votive offerings to the god and their public location displays how religion, even after the collapse of the Greek Empire, found itself in every sector of society, including theater.

The Chorus

One of the most perplexing elements is the prominence and role of the chorus and choregos. While it is often noted that the chorus was a integral part of Greek plays and festivals, there was no distinct guide to their size, demographic and even part in performances. Examining a specific vase (fig 4.), “The Choregoi,” from South Italy c. 380 BC, the posture, costuming and gestures of the portrayed characters exemplifies the important secondary role the chorus maintained (Green, 1999). It is important to consider the size limitations of such comic or phlyax vases; it would have been difficult to include an entire collective on the base of a sculpture and yet, the presence of such characters points to their significance. Just two men seem to represent an entire chorus comprised of wealthy young and old men, which would have been a luxury in the context of Athenian comedy. Comic plays during the time of—and even after—Athenian drama often held the role of the chorus in higher priority than tragedies. This may have been due to the “invention of a colourful and startling identity for the chorus” (Taplin, 1992, pg. 143), which one may find in the works of Aristophanes or Kratinos (Kaplin, 1992).

The preparation of the chorus and other aspects of play production relied on the beneficiary of an individual known as choregos. The term is comprised of two Greek words “chorus” and “to lead,” showcasing the central role the former had in these performances as a whole. Duties of the choregos, beginning with the dithyramb and eventually in tragedy or comedy were considered the second most expensive public service after the trierarchia (presenting a treime), a war gallery “with three banks of oars.” The choregos was responsible for the cost and labor of “recruiting, training and equipping the chorus” (Taplin, 1992, pg. 143), a task that resembled the preparing of soldiers for battle. The two men with identical sticks and costumes are emblematic of the chorus as a whole and their intricate robes and masks indicate a degree of funding and solid development on the part of the choregos (Taplin, 1992).

Vase Painting

Vase painting in Ancient Greece was largely comprised of two main creative conventions. Black-figure painting was a popular technique, which utilized slip that would blacken during the firing period leaving the remaining background light. More intricate paintings, such as the one displayed in Fig. 5, would include pigment mixtures of white or purple to enhance the intricate illustrations (Department of Greek and Roman Art, 2002). Red-figure vases differed from black-figure painting as the decorated icons or images would remain the color of the clay. The background, in contrast, would be coated in slip and turn black during firing. This technique may have been invented c. 530 B.C. by Andokides, a popular Athenian potter. It would slowly replace the original black-figure technique “as innovators recognized the possibilities that came with drawing forms, rather than laboriously delineating them with incisions” (Department of Greek and Roman Art, 2002). This progression displays the role of technology and innovation that coincided with this ancient process. Even to this day, potters rely on the wheel and kiln to bring their creations to life (Department of Greek and Roman Art, 2002).

Painting a Narrative Scene

Step One:

Drawing from inspiration (fig. 6), I started tracing the main components of my vase. To emulate red-figure painting, I outlined the whole piece (fig. 7) and painted it an orange-reddish color, resembling the color that the clay would be.

Step Two:

After letting the page dry, I painted the background black (fig. 8) to resemble what the final product would look like after the firing stage. Red-figure painting became a popular technique amongst ceramicists and artists as this second step allowed for more precise icons or decorations through the ability to outline in black. In contrast, black-figure painting consisted of the motifs (or “negative space”) being hollowed out and the outlines remaining the color of the clay.

Painting a Narrative Scene: Final Reflections

Although the act of painting a theatrical vignette on paper diverges from doing so on a pottery form, I attempted to emulate what ceramicists labored through by utilizing similar techniques. As I took on red-figure painting, I first washed over my entire “vase” with an orange-red color and then outlined the figures with black. I tried to stay within the same ceramics vein by using detail brushes and those that might be found in a pottery studio. The entire experience took around four and a half hours, which was partly due to the small-scale nature of my recreation. I definitely sensed how a flat surface also made this process easier than it would have been on an actual vase. However, I did find the exercise calming and, by the end, I felt as though I was capturing something important (even if I was referencing a photo). I started to understand why Athenians felt the need to document theatrical traditions as well as how toilsome it can be; theater served an extremely important social, religious and political role in Ancient Greece. And yet, I still wonder if there were any other underlying motives for creating such intricate forms of pottery. Painting a narrative scene opened my eyes to the other reasons why Athenian artists, or any artists may take on such a difficult task. Perhaps narrative vases simply acted as displays of artistry or mastery of ceramics; perhaps these pieces did not serve the sole purpose of recording performance traditions. Regardless, I am glad I took on this pursuit as it allowed me to enrich my research and incorporate a more hands-on approach to this topic.

Written Works Cited:

Department of Greek and Roman Art. “Athenian Vase Painting: Black and Red-Figure Techniques.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/vase/hd_vase.htm (October, 2002).

GREEN, J. R. “Tragedy and the Spectacle of the Mind: Messenger Speeches, Actors, Narrative, and Audience Imagination in Fourth-Century BCE Vase-Painting.” Studies in the History of Art, vol. 56, 1999, pp. 36–63. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42622232.

Hedreen, Guy. “The Return of Hephaistos, Dionysiac Processional Ritual and the Creation of a Visual Narrative.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 124, 2004, pp. 38-64. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3246149.

Sturgeon, Mary C. “The Reliefs on the Theater of Dionysos in Athens.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 81, no. 1, 1977, pp. 31–53. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/503646.

TAPLIN, Oliver. “THE NEW CHOREGOS VASE.” Pallas, no. 38, 1992, pp. 139-151. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43660651.

Images Cited:

Drost, Erik. Theatre of Dionysus. March 19, 2010. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Theatre_of_Dionysus_(5986568177).jpg. Accessed April 10, 2019. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Harrsch, Mary. Red-figured Bell Krater with Phlyax Theater Scene Greek made in Pulia South Italy about 380 BCE attributed to the Choregos Painter Terracotta. October 8, 2006. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/mharrsch/481800000/in/photolist-JziHd-Jzmmy-JziDG-JzmL6. Accessed April 16, 2019. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Orientalizing. Joust 1. January 6, 2018. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/orientalizing/31595015218/in/photolist-zQNNhu-eDAjPw-dqippA-pJ2pC9-DQYEjC-XzZiYf-Q8WHgG-97S7kY-97NWo8-97S9Ms-ZegvQG-97S86j-aJrGfT-WBqy1X-WBqyFe-7gJyYi-8XFCgV-nQHgvK-2cqzaf3-RaqGFB-dh5b17-7gNwao-2eLAZAd. Accessed April 16, 2019. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Signed by the potter Ergotimos and the painter Kleitias. Attic Black-Figure Volute-Krater, known as the Francois vase, ca. 570-565 BCE. March 25, 2017. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Attic_Black-Figure_Volute-Krater,_known_as_the_Francois_vase,_ca._570-565_BCE.jpg. Accessed April 10, 2019. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0..

Tarpoley Painter. Red-Figure Bell Krater with Satyr and Maenad. March 22, 2012. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tarporley_Painter_-_Red-Figure_Bell_Krater_with_Satyr_and_Maenad_-_Walters_482760_-_Side_A.jpg. Accessed April 21, 2019. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Videos Cited:

Getty Museum “Making Greek Vases.” November 19, 2010. Youtube. https://youtu.be/WhPW50r07L8. Accessed April 10, 2019.