An examination of works by Wole Soyinka and Tarell McCraney demonstrate how Yoruba tradition and cosmology adapted to survive cultural genocide and colonialism. Here, we will examine the path of conception, production, and synopsis as they retrace and reconquer the middle passage.

It’s a few minutes before 7:30PM in Waterloo on a Monday; February 5, 2018. I’m in seat F35 in the upstairs section of the main house of the Young Vic. I know this because the ticket is pinned to a cork board next to a picture from my sister’s high school graduation.

The stage is below us and surrounded on all sides by seating for the audience. It resembles a pit, a central black space below us. My classmate and I are passing the time with the playbill and we’ve narrowed in on the word “primal” in a starred review.

“I don’t want it to be primal,” she cringes. The lights go down.

The play opens with a ritual, an invocation of something the audience isn’t yet sure of. Three black men are on stage when the lights come up. They are Ogun Size, his brother Oshoosi, and Elegba. All of them are barefoot and all of them are plain clothed. Oshoosi size in fetal in the center, his brother standing over him and miming the act of hammering, punctuating each swing with a grunt. The ritual blends Elegba’s thrall “this road is rough…this road is rough and…it’s rough and hard…it’s rough…Lord God / It’s rough,” with the Size brothers’ actions while Elegba draws a circle in white chalk around them (McCraney, 158-159). There will be no props and no extras. Some of the dialogue is written in prose, some in verse. The white chalk circle will serve as the active space for the story.

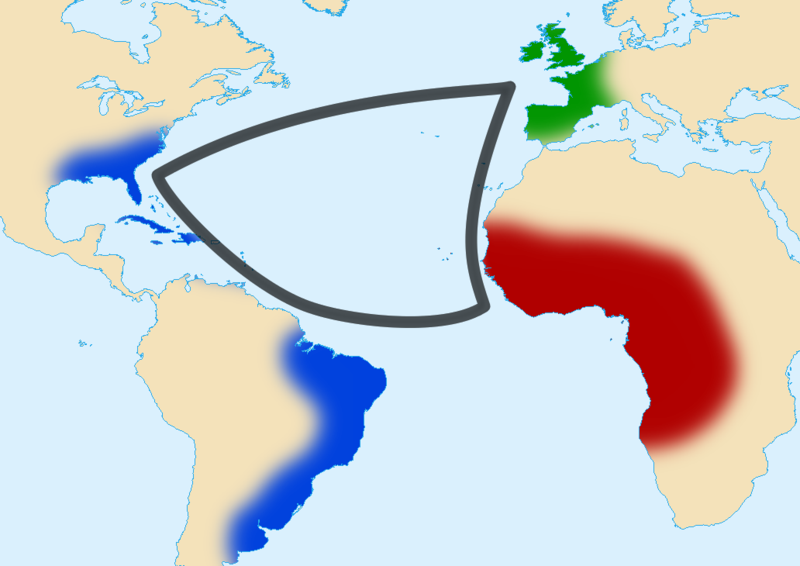

How does this play, about three black men in Louisiana, invoking Yoruba cosmology, come to be performed for the second time at this theater in Waterloo, London? What does it mean for these characters of this heritage to come to life on a stage in a city that completes the triangle of the route of the Atlantic slave trade?

In order to establish answers to these questions, I will trace the heritage of the slave trade by examining the influence of the Yoruba religion in three plays. Two of these plays are well-established, The Brothers Size and Death and the King’s Horseman, and a third play, The Meaning of Zong, set to be produced for the first time later this year. Although a script for The Meaning of Zong is not yet available and neither is much information regarding its production, it already represents an acknowledgement of London’s role in the transatlantic slave trade and an effort to decolonize theater by giving the story space to be produced. The Brothers Size is set in present day Louisiana, representing the American stop of the slave trade.

Yoruba cosmology and ritual

Ritual and play

Two of the major relevant themes in the Yoruba religion are ritual and play, both of which are represented in The Brothers Size and Death and the King’s Horseman. Much like theater, ritual is performed by knowledgeable agents (priests or local leaders) for a versed audience. That is to say, the audience knows something of what to expect from the physical and performative elements of the event—the play, the ritual. The Yoruba use etutu (ritual), festival, and play in an interchangeable sense, emphasizing that religious practices are active and require the community participation (Thompson Drewal, 12). Ritual is meant to connect the living world, the aye, to the orun, the invisible realm of spirits, ancestors and gods (Drewal, 69).

Play is different from ritual but the two are not mutually exclusive. To play a situation is to intervene in it, to assert oneself as a participant in the event and to alter it (Thompson Drewal, 12).

Cosmology

In my research, I have relied heavily on Henry John Drewal’s introduction to Yoruba cosmology. The Yoruba envision the cosmos as two inseparable but distinct realms—mentioned above as the aye (the visible, tangible world of the living) and orun (the invisible, spiritual realm of the ancestors, gods, and spirits)” (Drewal, 69). The cosmos are presented in the tangible world as either “a spherical gourd, whose upper and lower hemispheres fit tightly together, or as a divination tray with a raised figurated border enclosing a flat central surface” (Drewal, 69). An example of a divination tray is pictured right, with “images clustered around the perimeter of the tray” meant to represent mythic events of the orun and more quotidian events of the aye (Drewal, 69). These circular cosmos present a universe that is comprised of clashing and competing forces, and “the intersecting lines inscribed on the surface by a diviner at the outset of divination symbolize metaphoric crossroads, orita meta (the point of intersection between the cosmic realms)” (Drewal, 69).

Yoruba and the middle passage

The transatlantic slave trade was characterized by triangular trade. It is so named because the route of the slave trade resembled a triangle, beginning in West Africa where slaves were bought or captured. Slaves were then transported to the new world, if they survived the horrors of the middle passage, and forced to work in the harvesting and production of tobacco, sugar cane, and other resources. These were then exported to European nations and organizations who funded the slave trade and so the triangular cycle was repeated until (officially) the slave trade was abolished in 1807 (“Abolition of the Slave Trade”). The above image mapping the route of triangular trade color codes the process of the trade, with each major phase of the trade a different color. Millions of Yoruba peoples would have been uprooted and transported during this era, thus establishing legacies of the Yoruba religion in the New World—the Americas, Haiti, Cuba, Trinidad, and Brazil (Drewal, 68). The later arrival and massive numbers ensured that the Yoruba tradition would characterize and impact the artistic, religious, and social lives of slaves and their free descendants all over the world for generations to come (Drewal, 68). The route of this forced diaspora is particularly important for our analysis because it highlights each of the regions included in our study of Yoruba influence on contemporary theater. Death and the King’s Horseman, for example, is set in colonial Nigeria, part of the red region and representing the impact of colonialism in the homeland of the Yoruba people as it functions under colonial rule and after centuries of being vulnerable to the slave trade. In contrast, The Brothers Size takes place in the “distant present,” in Louisiana, part of the region colored blue on the map where the slaves were taken and where the vast majority of their descendants still live. Both plays have been performed in London, England, colored in green to indicate it as a historically major colonizing force, in the last ten years. These stories have long since arrived in realm of the colonizer and the significance of their productions is both a symptom of colonial history and a reckoning of England’s role in the slave trade.

Death and the King’s Horseman

Death and the King’s Horseman was written by Wole Soyinka, the first African to win the Nobel Prize for literature and premiered in 1975. The play was recently produced at the National Theater in London in 2009, a production noted for its use of “whiteface” on black actors to portray the white characters.

The Yoruba religious practices drive most of the plot and action in Death and the King’s Horseman. The premise of the play focuses on the Elesin, the best friend of the late king, as he enjoys his last day on earth before an intended ritual suicide in order to join the king in the next world and guide him to the afterlife. Elesin is, however, unable to let go of life and is prevented from completing the ritual by interfering English characters who represent colonial interference in tradition. When Elesin fails, both because of his strong connection to the earth and the intervention of Simon Pilkings, the local colonial and English authority.

A major element of the play is the omnipresence of the otherworld and the afterlife as events in the visual, human world play out. This manifests in the relationship between Elesin and the Praise Singer, with whom he has a playful relationship but also one in which he is vulnerable to a hypnotized and spiritual experience, where the Praise Singer communicates with him as a vessel of the afterlife (Soykinka, 35-36). The Praise singer is much like Elegba in The Brothers Size in that the manifestations of their relationships with their respective protagonists are playful and friendly but volatile, resulting in scenes in which Elesin and Oshoosi appear to be hypnotized by the musical and rhythmic dialogue of the Praise Singer and Elegba (McCraney 172-177; Soyinka 35-36). Drewal emphasizes this in his essay, writing “the importance and omnipresence of the otherworld in this world is expressed in a Yoruba saying: “the world is a marketplace [we visit], the otherworld is home” (Drewal, 72). Soyinka portrays this saying both in the overarching theme of his piece and also literally in the opening of the play, set in the marketplace (Soyinka, 5-18). The decision for Soyinka to place Elesin in the marketplace emphasizes that his time on earth is, by design, fleeting and that the day over the course of which the play takes place is meant to be transient.

Elesin is a character who loves life, in spite of the his duty to perform a self-sacrificing ritual at the end of what is meant to be his final day. He is a character whose duty is to join his friend, the dead holy king, in his journey to the afterlife but he cannot help himself from engaging in life. In the aforementioned marketplace scene, he pretends to be cross with the women, causing them to fret before he reveals he was not at all offended by them (Soyinka, 11-12). While in defiance of a Yoruba ritual and at the risk of massively disrupting the Yoruba cosmos, Elesin’s inability to commit the sacrifice as planned—due to his hesitation and subsequent kidnapping—is a way of playing the play in the Yoruba sense. He is interrupting the ritual, intervening in a situation, and altering it. Therefore, in failing to complete Yoruba ritual Elesin is participating in play and is embodied by play.

The Brothers Size

The Brothers Size was written during Tarell Alvin McCraney’s time at the Yale school of drama. The collection of the Brother/Sister Plays was published in 2010 as a triad of plays with overlapping characters and themes of Yoruba tradition. When I saw the play in London in 2018, it was the second time the play was being produced in The Young Vic theatre, the first production being when the play premiered.

The presence of the Yoruba tradition in The Brothers Size is keenly felt by the audience. In contrast to Death and the King’s Horsemen, the religion is a driving energy instead of scripted plot. The plot The Brothers Size is driven by modern American race relations with the looming presence of the American prison system, which disproportionately incarcerates men of color. The fusing of Yoruba themes with a modern day story about love and American race demonstrates the relevance and legacy of Yoruba culture and tradition that exists in America and the Caribbean because of the atrocious dispersal of bodies by transatlantic slave trade.

The three characters of the play are named for Yoruba orisas, deified ancestors or gods (Drewal, 69). The names of the gods contribute to the characters’ personalities as well as their relationships with each other. Ogun is the god of iron, which is presents itself in that the character is a hard-working car mechanic (Drewal, 70). Oshoosi’s name appears to be a variation of the name “Osoosi,” the god of hunting, and in the play he is characterized by his struggle to survive the American prison system and the racial biases of local law enforcement (Drewal, 70). Elegba is named for a trickster god, also a divine messenger and “activator” who stands “at the threshold between the realms of orun and aye, assisting in communication between the divine and human realms” (Drewal, 71). The characters’ driving traits and their interactions with each other are the result of the legacies of the orisas they represent. Ogun is characterized by his work ethic, introduced in the first scene of the play in which he demands his brother wake and come to work with him (McCraney, 142). Ogun describes his brother, “playin’ that’s what you always doin’,” which reveals his own perspective on hard work as much as Oshoosi’s attitude (McCraney, 155). Oshoosi, in response to his brother and freshly released from prison, is looking for liberation from work and routine in order to pursue life and happiness. Elegba is a non-traditional antagonist, setting major moments into play such as Oshoosi’s acquisition of a car and setting up Oshoosi to return to prison with him on the charge of drug possession. These characters are defiantly complex, struggling to survive. An added layer of this complexity is that in Yoruba cosmology “all gods, like humans, possess both positive and negative values—strengths as well as foibles” (Drewal, 70). That the orisas represented are not moralized is an important contribution to the characters, because it demands the audience realize that each of these characters is differently desperate—desperate to save themselves, desperate to save each other, and desperate to love each other as products of the racist system as a successor to colonial practices.

The circle in which the story is confined recalls the Yoruba world view, a circle with intersecting lines (Drewal, 69). This cosmological circle, in which the access to the divine is within the boundaries, recalls the circle drawn in white chalk by Elegba in the opening invocation. Traditionally, a priest draw the lines to “”open” channels of communication before beginning to reveal the forces at work and to interpret their significance for a particular individual, family, group, or community” (Drewal, 69). The three actors are performing an altered ritual in the drawing of the circle in white chalk on the floor, and the circle’s role in serving as the boundary of the story signposts the influence of Yoruba cosmology on the play. Drewal writes of the lines, “the manner in which they are drawn (vertical from bottom to top, center to right, center to left) shows them to be three paths—a symbolically significant number…Thus the Yoruba world view is a circle with intersecting lines” (Drewal, 69). The number three is significant here, as there are three lines intersecting on the Yoruba cosmic plane representing three paths; these paths are perhaps represented by each of the three characters in the play (Drewal, 69).

Similarly to Elesin in Death and the King’s Horseman, Oshoosi and Ogun engage in play. In order to cheer up his brother, Ogun and Oshoosi play music and dance together, Ogun pretending to play an instrument and Oshoosi singing and dancing (McCraney, 230-234). When Elegba appears at the window and, in the spirit of his namesake, activates a fear and alertness in Oshoosi (McCraney, 234). Oshoosi says to Ogun, “I don’t want to play no more,” and one of the spare lighthearted scenes of the play is gone (McCraney, 234).

A haunting but subtle moment in the script is Oshoosi’s speech to Ogun, recalling the connection he felt to a photograph he had seen of a black man in Madagascar while he was in prison.

McCraney, 203

“This man…this nigga…this man…he look just like me! I swear somebody trying to fuck with me…Legba or the warden done got a picture of me and stuck it in this book about Madagascar with me half naked n shit…But it ain’t! Him and me could’ve been twins man! He standing and you know what he saying…What it look like he saying? “Come on let’s go.” I can see it in his eyes! I need to be out there looking for the me’s. He got something to tell me man. Something about me that I don’t know ‘cause I am living here and all I see here are faces telling me what’s wrong with me.”

This passage emphasizes the daily struggle of black and brown bodies in America, constantly seeing “faces telling me what’s wrong with me,” as Oshoosi puts it. He feels a connection to the African man in the photograph and is attempting to articulate that he feels this other man, who resembles him, knows something about the world or life or happiness that he himself does not know. The connection between Oshoosi and the man in the photograph recalls the slave trade and the transportation of slaves from Africa to the new world. The play takes place in Louisiana, across the world, but Oshoosi is imprisoned not just in jail but in a country that systematically oppresses him and men and women who share his identity.

Coming Soon: The Meaning of Zong and Bristol

England and the west are still coming to terms with acknowledging their colonial history, and theater is part of that reckoning. In Bristol, the Old Vic reopened at the end of last year after a £25m renovation, creating a new entrance to the theater and a refreshed auditorium (Thorpe). With the publicity attached to the renovation and reopening of a theater that is more than 250 years old, the artistic director, Tom Morris, announced that with the reopening of the theater’s doors there is a renewed sense of responsibility (Thorpe). Morris to take responsibility for the fact that the wealth that contributed to the construction of the theater most likely came from the “economic boom” that was the slave trade (Thorpe). Morris said that the year following the reopening of the Old Vic is “the Year of Change and it has been about renewing our relationship with the city” (Thorpe). Other establishments in Bristol are also following suit, as nearby Colston Hall announced that it would be revising its name “before a relaunch in 2020, thereby dropping a long association with a prominent slave trader, Edward Colston” (Thorpe).

Also at the end of 2018, award-winning actor Giles Terera staged a workshop of his upcoming play, The Meaning of Zong, which will be about the 1781 massacre of slaves on the slave-ship Zong. The significance of not only the staging of this workshop but of the production of the play set to premiere in the spring of 2019 is a massive step for English theater as it attempts a vessel of decolonization by acknowledging a problematic history and striving to make the theater a more honest and inclusive space for those of african and afro-caribbean descent. While the script is not yet available and the play will not be fully staged until later in 2019, a review of the workshop states, “Giles Terera has constructed a story that expertly covers the harrowing experience that the slaves experienced without resorting to excessive violence or becoming too depressing” (“The Meaning of Zong – Workshop Review”).

Final Thoughts

I opened this piece by disclosing my own personal connection to The Brothers Size. I walked out of the theater in tears, calling my younger sister who was alarmed by my surge of affection from the other side of the world. These works are powerful because they employ their heritages in order to convey stories that are far more universal: family, the bond between siblings, and confronting colonial legacies and the long-lasting impact of the transatlantic slave trade. By now, I hope it is clear that seeing the production of The Brothers Size at the Young Vic had an undeniable impact. The power of the play’s minimalism, rhythm, and larger message sets a standard for contemporary theater to be political, inclusive, and more than just a story. My hope is that this study of Yoruba themes present in plays written decades apart and situated across the ocean from each other connects and remembers the separation of a population from their home by colonial practices. The production of The Meaning of Zong opens the door for this topic to be researched further by future Global Theater students and theater academics as western theater decides its past role in promoting colonial practices and its future responsibility to decolonize.

References and Research

- “Abolition of the Slave Trade.” Black Presence, The National Archives, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/rights/abolition.htm.

- Barber, Karin. “Literature in Yorùbá: Poetry and Prose; Traveling Theater and Modern Drama.” The Cambridge History of African and Caribbean Literature, edited by F. Abiola Irele and Simon Gikandi, vol. 1, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000, pp. 357–378.

- Drewal, Henry John, et. al., excerpt from The Yoruba World in Death and the King’s Horseman, 66-73.

- Drewal, Margaret Thompson. Yoruba Ritual: Performers, Play, Agency. Indiana University Press 1992.

- McCraney, Tarell Alvin. The Brother/Sister Plays. Theatre Communications Group, 2010.

- National Theater. “Rufus Norris on Death and the King’s Horseman.” YouTube, 19 May 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=RXgYPOL0gbY.

- Soyinka, Wole. Death and the King’s Horseman. 1975.

- “The Meaning of Zong – Workshop Review.” Home Brewed Reviews, WordPress.com, 18 Oct. 2018, hbreviews.home.blog/2018/10/15/the-meaning-of-zong-workshop-review/.

- Thorpe, Vanessa. “New Life for Historic Theatre as It Faces up to ‘Slave Trade’ Past.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 9 Sept. 2018, www.theguardian.com/stage/2018/sep/09/bristol-old-vic-slave-trade-theatre-reopens-25m-facelift.

- wildwatertv. “Brothers Size.” YouTube, 11 Sept. 2008, www.youtube.com/watch?v=gAPnQSJKFHs. Made with support from The Genesis Foundation.

Media and Images

- “Divination Tray (Opon Ifa).” Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia.org, 31 Oct. 2012, upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0c/Brooklyn_Museum_75.147.1_Divination_Tray_Opon_Ifa.jpg.

- National Theater. “Rufus Norris on Death and the King’s Horseman.” YouTube, 19 May 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=RXgYPOL0gbY.

- “Slave_Ship.” Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia.org, 15 Mar. 2014, upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/26/Slave-ship.jpg.

- “Triangular Trade.” Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia.org, 14 Apr. 2007, upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ac/Triangular_trade.png.

- wildwatertv. “Brothers Size.” YouTube, 11 Sept. 2008, www.youtube.com/watch?v=gAPnQSJKFHs. Made with support from The Genesis Foundation.

- “Young_Vic.” Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia.org, Waterloo, London, 21 Apr. 2007, upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c0/Young_Vic.jpg.