Overview: Kabuki Theater is one of the most influential forms of creative expression in Japan because of its inclusive nature and dynamic use of costume, staging and dance. In examining, the play “Just a Minute!” by Fukuchi Ōchi, we intend to demonstrate the elaborate theatrical elements that are involved in this type of theater. We used this play as inspiration for the creation of our own rendition of the Kumadori makeup style.

Introduction:

Kabuki theater is an incredibly popular traditional Japanese drama which includes both singing and dancing as well as a combination of elaborate costumes and makeup. Kabuki is translated to mean unorthodox or shocking. This title stems from the genre’s use of intricate and eye-catching makeup and costumes. Our website analyzes the importance of Kabuki theater throughout history and highlights the different forms of Kabuki, with a specific focus on Kumadori makeup, the intricacies of costumes, and the dynamic stages used in this form of theater. To further understand this form, we examined “Just a Minute!,” a popular Kabuki play. In engaging with the text, we were able to better understand the mechanisms used in performance and concretely demonstrate the importance of theatrical elements in the success of the play.

Just a Minute!

Like other Kabuki plays, “Just a Minute!” focuses on the importance of integrity and the triumph of heroes. The performance opens with the “face-showing” ceremony during which the actors introduce the play and reveal their characters. This portion of the play acknowledges the fact that it is a theatrical experience and breaks the fourth wall in doing so. The play opens with the antagonist, Takehira, who reveals that he is taking control of the land and will kill anyone who opposes him. While a few of the characters oppose this and label him as a tyrant, many of the members of the crowd support him. Takehira decides that he wants to marry a young woman named Katsura who is already engaged to Yoshitsuna, a young man who has become disinherited. Since Katsura refuses to marry Takehira, he threatens to kill both her and her fiance. He sends his samurai, who are referred to as the “Belly-thrusters” to kill the lovers. Right before they are able to commit the act, a voice shouts “just a minute,” which confuses the crowd and samurai. They question who is yelling and wonder where the voice is coming from. It begins to increase in volume and severity and the men are concerned. Then, Kagemasa, the hero of the play, reveals himself and threatens the samurai, telling them that he will kill them if they murder Katsuna and Yoshitsuna. Ultimately, Kagemasa protects the couple and one of Takehira’s followers, Teruha, reveals himself to be a spy for Kagemasa. Teruha reveals that Takehira was involved in Yoshitsuna’s disinheritance and Katsuna and Yoshitsuna exit safely. Like most Kabuki plays, the hero ultimately prevails and justice overpowers immorality.

History

1600-1603: The Origin of Kabuki

Originating between 1600 and 1603, early Kabuki theater took the form of controversial songs and dances that were created by a woman named Okuni and her company of actors and actresses (Brandon & Leiter, 1). Elements like cross-dressing and suggestive dance routines increased Kabuki’s popularity among the masses as well as its infamy among government officials. Okuni’s performances were characterized as “deviant” or “slanted,” resulting in the name Kabuki (Brandon & Leiter, 1). The seductive and irregular nature of the performances ultimately resulted in their censorship as the government banned women from partaking in theater. Although Kabuki was founded by a woman, it developed into a theater for strictly men with young boys and men quickly filling the roles that were traditionally held by women. This form has lasted until the present day. While the earliest performances of Kabuki were popular, the form truly flourished and developed from 1697 until 1905.

1773- 1799: The Golden Age of Kabuki

Early Kabuki performances resembled the traditional Noh plays in the sense that their stages were relatively plain (Brandon & Leiter, 3). Over time, Kabuki playwrights began to utilize both staging and costume design as other mediums to convey the story through. These plays became very focused on elaborate stages and luxurious costumes that would shock the audience. Playwrights were focused on evoking a spectacle, competing with one another to create the most extravagant play possible. This emphasis on the performance aspect of the play resulted in drastic innovations to the stage such as the creation of the hanamichi and the revolving stage. This period is characterized as being captured by the “aesthetic of cruelty” since the sets, costumes and music made moments of violence and pain seem beautiful and intriguing (Brandon & Leiter, 8).

1804- 1864: The Dark Period

Like other forms of theater, Kabuki was impacted by the political climate of the surrounding area. Kabuki was initially created during the era of the Tokugawa shoguns. Under their rule, Kabuki flourished and a large number of theaters were built in the major cities of Japan. With the onset of famine, Japan suffered from various revolts that threatened the foundation of the feudal system enforced by the Tokugawa shoguns (Brandon & Leiter, 8). This tumultuous political climate resulted in plays that focused on “darkness and sexual desire” from 1804 until 1864 (Brandon & Leiter, 8).

1872-1905: The Meiji Restoration

Kabuki theater was impacted by the Meiji restoration during which the feudal system was abandoned and the Meiji emperor was restored to power. During this period, the emperor abolished isolationism and Japanese culture began to embrace Western traditions and ideals (Brandon & Leiter, 8). For the first time, Japanese theater was exposed to the influence of Western drama. The Meiji emperor attempted to restrict and Westernize various traditional elements of Kabuki, but was unsuccessful. As a result, modern Kabuki theater contains influences of Western drama while still retaining many of its unique conventions. Eventually, the Meiji emperor supported Kabuki and named it the official form of entertainment in Japan.

Kabuki in the Present

After 400 years, Kabuki remains a prominent feature of traditional Japanese theater (Martin). While the theater has been a relatively prominent feature of Japanese entertainment, there have been periods when its prominence was weakened. During World War II, the popular Kabukiza theater was destroyed, which negatively impacted Kabuki’s popularity among the masses. However, the theater was rebuilt and its popularity was restored. Overtime, the theater has embraced a variety of Western techniques such as the use of “earphone guides,” which were added to the performances in 1975 to make them more accessible for older audiences (Martin). Similarly, in 1982, English translations of the major plays were created. While these improvements have helped kabuki assimilate into modern society, the Shochiku Co. has worked to promote the form by managing the Kabukiza theater in Tokyo and staging performances (Martin). Similarly, the Kabukiza was able to boost kabuki’s popularity by staging year-round performances in 1991 (Martin). Finally, in 2005, the Shochiku company began tocreate “cinema kabuki,” in which the performances became movies and were projected on a screen (Martin).

Common Themes of Kabuki Plays

Unlike Noh plays which were associated with the upper classes, Kabuki plays were adapted for a popular audience. These plays were written in the vernacular and focused on universal themes like duty, power, love and the acquisition of wealth (Brandon, 34). In structuring these plays so that they were accessible to a wide range of audience members, Kabuki opened the theater for both the middle and lower classes. Similarly, since Kabuki theaters were located in various urban centers like Edo, Osaka and Kyoto, they often focused on topics that were relevant those areas. For example, plays performed in Edo were impacted by the abundance of samurai in the city whereas plays performed in Osaka were influenced by the city’s wealthy merchant class (Brandon & Leiter, 2). While Kabuki plays are relatively open in their themes, they are limited by the censorship of representing true historical events. The government has restricted the recreation of historical figures and events from being represented in the theater, so Kabuki playwrights often use abstraction to overcome this barrier. This is particularly noticeable in the historical, Jidaimono plays. By abstracting the plot and setting of the play, the playwright is able to comment on specific historical figures or events will remaining within the constraints of the censors.

Kabuki Performances and the Audience

In terms of the performance, Kabuki engages with the audience to fully surround them in the play. Prior to the show, musicians will play drums so that they sound throughout the theatre. This traditional element of Kabuki serves as an auditory cue that the theatre is opening and that the audience should arrive quickly. As the performance approaches, dekata or ushers will guide the audience members to their seats as musicians play the flute and drums in the background (Kincaid, 9). This is intended to draw the audience into the excitement of the play and surround them in its environment. The audience sit on cushions that are grouped into boxes of no more than four people, creating an intimate environment throughout the theater (Kincaid, 9). Kabuki programs are intended to be pleasurable experiences for the audience and there are refreshment vendors that line the theater so that everyone is comfortable during the performances (Kincaid, 14). Unlike many forms of Western plays, Kabuki programs do not run on a strict timeline. However, they typically begin at three o’clock in the morning and end before dusk (Brandon, 24). This allows for the playwrights to incorporate all of the details they desire into the performance.

The 4 Forms of Kabuki

Kabuki theater can be divided into four subsections that are each distinct from one another: jidaimono, sewamono, shosagoto, and aragoto (Kincaid, 253). While Kabuki, as a genre, stresses the importance of innovation, their programs are relatively prescriptive. Traditionally, the performance will open with a jidaimono play then cut to a middle curtain. Then, the theater will put on a short performance (often in the aragoto style) which is followed by a sewamono play. The program typically concludes with a dance that includes that young actors (Kincaid, 254-255).

Jidaimono: Jidaimono are historical dramas that typically open Kabuki programs. These performances tell stories of historic heroes and heroines. Since the government restricts theaters from commenting on true historical figures, jidaimono plays are heavily abstracted (Kincaid, 253). These plays are often set in imaginary locations and follow strange, unrealistic plot lines. By obscuring the play through these abstract elements, the playwright is able to represent the historical event in an abstract context. This abstraction allows the audience to view the historic event or person in an academic context, which lets them comment on them.

Aragoto: The aragoto form which translates to “rough acting,” is the most abstract of the four forms of Kabuki (Kincaid 254). These performances are mainly improvisational and are not considered to be representative of drama as a genre. This form emphasizes the dynamic nature of acting and relies heavily on the actors’ onstage choices. Aragoto plays are characterized as being over the top and are very dramatic in their use of visual elements like costume and makeup. “Just a Minute,” is a popular aragoto-style Kabuki performance from the Tokugawa period in Japanese history. This play focuses on a young hero who saves various characters from the hostility of Kiyohara No Takehira, an evil nobleman. Like many Kabuki performances, this play opens with the announcement ceremony, in which the young actors are called out onto the stage by an elder member of the company (Kincaid, 40).

Sewamono: Sewamono plays are characterized as “plays of everyday life” that focus on the joys and sorrows of human nature (Kincaid, 253). These plays are the most similar to Western plays since they are less focused on abstraction. Popular sewamono plays were typically stories of prostitutes and their attempts to garner wealth. These plays became particularly popular from 1804-1864 as a result of the political unrest that was sweeping through the nation. During this period, sewamono plays were called kizewamono or “true sewamono” since they were revealing the corruption and economic disparity across different regions (Brandon, 21).

Shosagoto: Shosagoto plays, which also go by the name of furigoto, are music-posture dramas (Kincaid, 254). These performances are considered to be the most representative of Kabuki as a whole since they combine many theatrical elements in their performances. Since shosagoto plays give equal weight to the importance of the plot, music, acting, scenery, movement and color used in the piece, they are truly representative of Kabuki as a theatrical form. These performances also often take the form of dance sketches and serve as the finale to a Kabuki program. In this case, the dance showcases the physical appearance of the actors and highlights their femininity (Brandon, 19).

Staging and Costume Design

Both staging and costume design play a critical role in the execution of Kabuki theater as everything on stage is important and all props are placed in specific areas for a reason. Kabuki costumes are created using bright colors and patterns as a way to create a dramatic effect on the performance. The costumes are known to be quite heavy, often weighing over 20 kilograms, including many intricate folds and layers that need to be placed correctly during the performance so that the actors can move across the stage freely. An important aspect of costumes for both male and female characters are wigs, which are created by specialized craftsmen who make the wig according to the shape and size of each actor. These intricate details about costumes are important to consider as costumes and the process of costume changes during the performance are critical to the execution of each performance. Often the actors do a “quick change” and transition to the role of a different character through the means of a costume change.

The importance of costume design is reflected in “Just a Minute” since the elaborate clothing is used to demonstrate good versus evil. For example, the hero Kagemasa wears what is characterized as wearing the most famous of Kabuki costumes. He is dressed in “a hugely oversized, persimmon-colored outer garment whose square, winglike sleeves are decorated with the Danjūrō crest” (Brandon & Leiter, 24). The stage directions note that he wears clogs that increase his height and a huge sword. These details are intended to reflect Kagemasa as a truly heroic character and would have been consistent with the appearance of other heroes. Similarly, Takehira is revealed as evil through his appearance. Aside from the makeup, he wears a “large black wig parted in the middle with a gold crown” (Brandon & Leiter, 20). In terms of clothing, he is clad in all white and holds a fan and ledger. The difference in costume between evil and heroic characters is very apparent and serves as a visual aid in distinguishing character. This play also demonstrates the importance of the quick change since Kagemasa periodically changes his costumes in front of the audience. Like the music and setting, the costumes are altered to reflect the action of the play at each specific moment. The combination of the music, dance moves and costumes associated with certain characters reveals the true intentions of each character on the stage.

The stages in Kabuki are another interesting aspect of theater to analyze. Many of the earliest known kabuki performances were performed on temporary stages. Overtime, the stages became more complex and in 1896, a full-size revolving stage was used in Europe for the first time. The notion of revolving stages became popular quickly; this complex feature allows for three or four scenes to be extended by moving the stages to the left or right so that different characters can easily enter and exit the stage. The pictoral effect of the stage in Kabuki is important as well and the use of vibrant colors are eye-catching and are meant to resemble nature. The combination of the elaborate costumes as well as a detailed stage design are important aspects of the Kabuki performance that make it even more fascinating and entertaining to watch.

“Just a Minute!” demonstrates the effects of transforming the Kabuki stage. The play utilizes many of the innovations that were created during the Golden Age, such as the hanamichi, to enhance the story-telling aspect of the performance. In this play, the hanamichi walkways are decorated with dance platforms that allow the actors to demonstrate their character’s personality as they walk onto the stage. The stage directions provide clear instructions on the movements that specific characters are to make. These directions also indicate the specific transformations that are to take place on stage. At the command of specific music notes, a wall “opens from the center,” and the characters appear from the middle of the stage (Brandon & Leiter, 20). This deconstruction of the stage reveals a shrine and changes the setting. Like other Kabuki plays, “Just a Minute,” contains long paragraphs of stage directions that are essential to the play’s success. These directions not only indicate the specific of movements necessary, but also the type of costumes and set design.

The Kumadori Makeup

After a deep analysis of Kabuki theater, it became evident that makeup is one of the most essential and impressive aspects of the performance. The process of applying makeup allows the actors to gain a better understanding of the character they will be playing, as each actor applies his or her own makeup for the performances. The process of applying the makeup requires keen focus and attention to detail. The first step is to apply oil and waxes to one’s face in order to help the white makeup, called oshiroi, stick to the skin and cover the actor’s entire face. Historically, this white makeup allowed actors to be better seen on stage before electricity had been invented, but it is also intended to create a dramatic appearance for the actors on stage. The shades of white vary and are used to distinguish different actors based on age, class, and gender. Red and black lines are used as accents on the white face and vary depending on the gender of the actor.

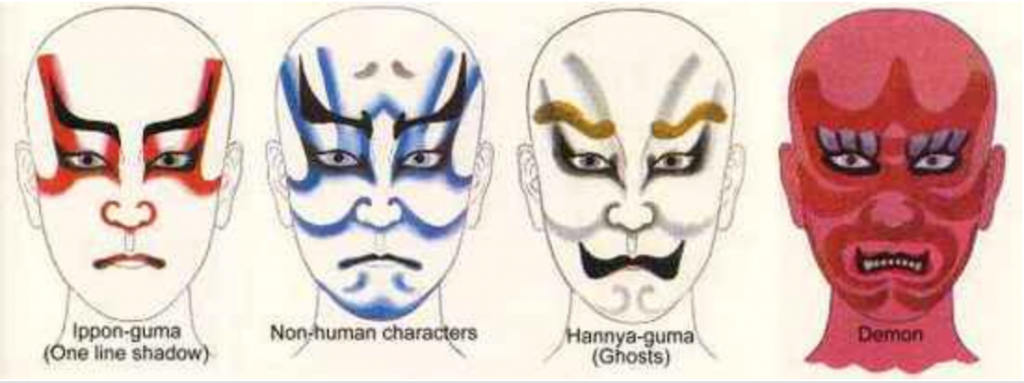

The Kumadori makeup is a more specialized form of makeup that is used for supernatural heroes and villains and includes dramatic lines and shapes applied using a variety of colors. The color choice is important to analyze because the colors are selected to represent different emotions, such as dark red to indicate anger and passion, and dark blue for sadness or depression. More specifically, there are certain styles of makeup to represent each character and distinguish between them. For instance, Samurai are accepted to have dead white, with broad black eyebrows and touches of red to the eyes and corners of their mouths. Villains are depicted using blue faces whereas country people are typically shown with brown faces. Strong and courageous warriors typically are seen with a grey chin, red lips with a white border, and then have strokes of red from their eyes and cheeks up until near their foreheads. They also have a distinguishing feature of raised eyebrows, which is representative of their anger. Brave men have very distinct makeup as well, and their makeup is supposed to represent retaliation, which is shown with broad red lines with a subtle pink shading around the eyes. It is evident from these various descriptions that makeup plays a crucial role in distinguishing characters from one another. As demonstrated in the video below, the differences in makeup are immediately noticeable and are helpful in distinguishing the characters from one another. The speaker notes that the well-mannered brother wears white, simple makeup to reveal his passive nature whereas the other brother wears exaggerated makeup to demonstrate his more explosive personality.

Like the production presented in the above video, the use of Kumadori makeup is essential to the production of “Just a Minute!”. Takehira, the antagonist of the performance is painted with blue makeup to demonstrate that he is a villain and his stomach is outlined in black lines to show his muscular appearance (Brandon & Leiter, 20). Kagemasa wears the typical heroic makeup, which consists of a white face with red lines. Like all other Kabuki plays, the makeup is essential to the personality of the character and is intended to blend in with all other aspects of the performance.

Our Attempt in Creating Kumadori Makeup

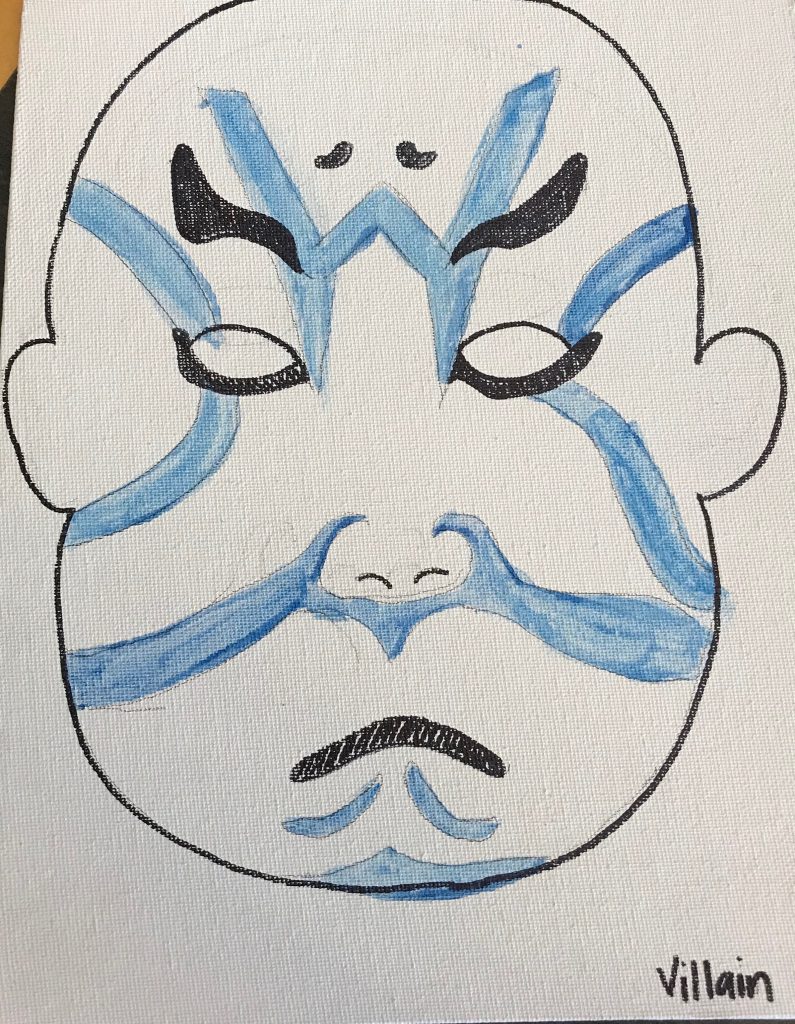

We decided to recreate some Kumadori styles since makeup plays an essential role in the performance of Kabuki plays. In creating these images, we consulted the “Kabuki” Youtube video as well as the images of Kagemasa that we found online. Since “Just a Minute!” contains a villain and a hero, we decided to create images of a basic hero (Figure 9) and a basic villain (Figure 10). Figures 9 and 10 serve as templates for these types of characters. These serve as the basic renditions and artists often diverge from them. However, the patterns and colors are relatively consistent. To continue our engagement with “Just a Minute!,” we decided to include a recreation of Kagemasa’s makeup (Figure 11). Like the template hero, his face is patterned with red lines and he has large, darkly filled eyebrows. The contrast between the hero and villain is very apparent in both the coloring and design of their makeup.

While we have read about the precision that is essential to Kumadori makeup, we were surprised by how challenging it was to recreate the makeup styles. Each style requires the lines and angles to be accurate since the patterns are intended to create a sort of fluid look. Drawing the patterns in the correct proportions was very difficult and incorrect spacing was immediately noticeable. We found that the three styles required lines that were both rigid and smooth, which was a hard element to create visually. In terms of creation, the villain was the easiest style to draw and the Kagemasa makeup was the hardest. Styles with less lines, or lines that have a distinct beginning and end were the easiest to draw. The experience of creating these looks was very rewarding since it reminded us of how much work is dedicated to creating these spectacles. Similarly, it reinforced our appreciation for this type of theater since it reveals the extreme level of detail that goes into each element of the performance.

Why is this Important?

With between 250 and 300 plays and dances, Kabuki is one of the most popular forms of traditional Japanese theater (Brandon & Leiter, ix). However, less than 20 of these plays have been translated into English, making Kabuki a relatively under-appreciated form of entertainment among Western audiences (Brandon & Leiter, ix). Since Kabuki plays are written in a conversational language that evolved with time, it is difficult to create accurate translations of the plays. Likewise, many scholars do not perceive Kabuki to be a true literary form because of its reliance on theatrical elements like costume, makeup and staging. Since they do not see its literary value, they refuse to translate and engage with the plays. This perception of Kabuki is very limited and does not accurately depict the level of detail and thought that is necessary for each performance. In creating this webpage, we hope to create greater awareness of this form of theater since its long-standing and dynamic history makes it an important part of global theater. Similarly, we hope that this page brings awareness to the importance of theatrical elements and their significance in plays. While these elements are often regarded as aesthetic choices, they are strategically chosen for the performance and demonstrate significance to the play’s meaning. In analyzing plays, it is essential that we do not disregard the importance of these elements and rather celebrate them. Similarly, we hope that this webpage demonstrates the importance of respecting all types of theater and that our analysis of Kabuki will inspire others to engage with other forms of theater that are widely under-represented and under-appreciated in studies of global theater.

Literary References

- Brandon, James R. “Preface and Introduction.” Kabuki: 5 Classic Plays, Harvard Univ. Pr., 1975, pp. vii-47.

- Brandon, James R., and Samuel L. Leiter. “Introduction.” Masterpieces of Kabuki: Eighteen Plays on Stage, University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2004, pp. ix-15.

- Brandon, James R., and Samuel L. Leiter. “Just a Minute!” Masterpieces of Kabuki: Eighteen Plays on Stage, University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2004, pp. 18-33.

- Hays, Jeffrey. “KABUKI: HISTORY, THEMES, FAMOUS PLAYS AND COSTUMES.” Facts and Details, 2009, factsanddetails.com/japan/cat20/sub131/item715.html#chapter-10.

- Kabuki Makeup.” Fashion Encyclopedia, Advameg, 2019, http://www.fashionencyclopedia.com/fashion_costume_culture/Early-Cultures-Asia/Kabuki-Makeup.html.

- Kincaid, Zoe. Kabuki: the Popular Stage of Japan. Benjamin Bloom, 1965.

- Lombard, Frank Alanson. “Kabuki: A History.” Theatre History, 2002, www.theatrehistory.com/asian/kabuki001.html.

- Maki, Isaka. Onnagata: A labyrinth of gendering in kabuki theater. University of Washington Press, 2016.

- Martin, Alex. “Kabuki Going Strong, 400 Years On.” The Japan Times, 28 Dec. 2010, www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2010/12/28/reference/kabuki-going-strong-400-years-on/#.XL5i0ZNKhdg.

Visual References

- “A Quick Introduction to Understanding the Riddles of Kabuki – Japan Info.” Japan Info, UNESCO, University of Wisconsin, 1 Feb. 2016, jpninfo.com/41121.

- “Kabuki.” Theater 162 – Digital Portfolio, theater162digitalportfolio.weebly.com/kabuki.html.

- “Kabuki”. Youtube, uploaded by cae12810, 27 January 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlTQUzPZU8Y&t=8s. Video was trimmed from 1:20-2:32.

- Kuniume. “A kabuki theatre during a performance: three actors from the Ichikawa line perform a traditional play to an inattentive audience”. 1884. Wellcome Collection Gallery. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_kabuki_theatre_during_a_performance;_three_actors_from_the_Wellcome_V0047371.jpg. Accessed 14 April 2019. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- lensonjapan. “Children kabuki theater in Nagahama (lady Shizuka, 10 y.o.)”. 15 April 2013. Flickr. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Children_kabuki_theater_in_Nagahama_(lady_Shizuka,_10_y.o.);_2013.jpg. Accessed 14 April 2019. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

- Nesnad. “Kabuki Traverse Stage”. June 16, 2017, National Theater of Japan. Accessed 8 April 2019. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:National_Theatre_of_Japan_-_Hanamichi_2018_10_21.JPG Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Okumura Masanobu. “Perspective View of the Interior of the Nakamura Theater with Ichikawa Ebizo II as Yanone Goro”. 1740. Cleveland Museum of Art. https://clevelandart.org/art/1916.1154. Accessed 10 April 2019. Cleveland Museum of Art. Licensed under [CC0].

- Pelagalli, Carlo. Kabukiza Theater. 15 July 2008.. Tokyo, Japan. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kabukiza_Theater_-_panoramio.jpg. Accessed 22 April 2019. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Tadakiyo, Torii. “Kagekiyo: Ichikawa Danjūrō IX as Kazusa Akushichibyōe”. 1895-1896. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kagekiyo,_from_the_series_The_Eighteen_Great_Kabuki_Plays.jpg. Accessed 11 April 2019. Licensed under PD-US-expired.

- Tōshūsai Sharaku. “Ukiyo-e hosoban print of the kabuki actor Ichikawa Ebizō I as Gongorō Kagemasa”. 1794. Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sharaku_(1794)_Ichikawa_Ebiz%C5%8D_I_as_Gongor%C5%8D_Kagemasa.jpg. Accessed on 14 April 2019. Licensed under {PD-Japan-oldphoto} Public Domain Mark 1.0.