Overview: The Flower Princess and Rouge were both widely popular performances meant to help Hong Kong forge its own unique identity. While the performances differ in context and form, they are equally contradictory in their function as byproducts of colonization and tools to grapple with an overwhelming sense of nostalgia.

Unpacking Nostalgia in Chinese Performance

Much of Chinese performance functions on cultural critic Rey Chow’s concept of “primitive passions.” Chow argues that primitive passions happen whenever a series of steps take place. Firstly, the interest in the primitive emerges at a moment of cultural crisis—at a time when traditional culture is being dislocated due to vast changes in society. Because of this quickly changing environment, fantasies of an origin emerge; symbols begin to emerge to materialize the something lost. This fantastical origin is then reconstructed as a familiar common point of knowledge—an irretrievable place that everyone seems to have once experienced. This imagined primitive place provides a therapeutic way for thinking about the present, the future, and the “unthinkable.” The “unthinkable” is what was once basic and universal to us all, outside of time and language and tradition. But, because the primitive commonplace only exists in an imaginary space, it is quite literally “phantasmagoric,” or created by a collective dream (Chan & Willis, 2016).

“This origin is… reconstructed as a common place and a commonplace, a point of common knowledge and reference that was there prior to our present existence. The primitive, as the figure for this irretrievable common/place, is thus always an invention after the fact—a fabrication of a pre that occurs in the time of the post.”—Rey Chow, 1995

In the context of twentieth century China, torn between “first world imperialism” and “third world nationalism,” a paradox takes form. Chinese culture is viewed as “primitive,” or stuck in a space closer to nature than to modernization, because it is “less modern” than the West, but also because it existed in an ancient age pre-dating the West and colonialism altogether. Rey Chow argues that, in the case of China, primitivism means both being the dejected “victim” and the glorious “empire” (Chan & Willis, 2016). This paradox emerges in both The Flower Princess and Rouge, resulting in performances that romanticize the unattainable past while simultaneously pointing to its nuanced problems. These two different types of performance work to detangle the complicated mission of forging an identity post-trauma, showing the ironies and power in meaning-making art.

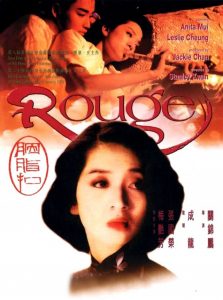

Cinematic Memory in Rouge

Stanley Kwan’s Rouge is a film that circles around the ideas of disappearance, love, and time. The film was released in Hong Kong in 1987, three years after the Sino-British Joint Declaration Agreement was signed by the PRC and the UK. With this agreement, Hong Kong was set to be returned to Mainland control in 1997. In the period between 1984 and 1989 particularly, an air of uncertainty washed over Hong Kongers as to what the territory’s future held. This period of uncertainty bred a period of films in Hong Kong that looked back on the past and resurged period dramas, like Tsui Hark’s “Peking Opera Blues” and Wong Kar Wai’s “Days of Being Wild.” These films also viewed the future with a skeptic and cynical lens, already mourning for a lost past (Leong, 1999). However, Rouge was one of the few films produced in this period that chose to interrogate nostalgia more carefully and gaze ahead with a more optimistic view.

The film is a mixture of tragedy and romance that incorporates elements of the supernatural. Rouge oscillates between two love stories told in different time periods. In the 1930s, Fleur is a courtesan who falls in love with the lucrative Twelfth Master. Their relationship is forced to come to an end when the Twelfth Master is made to marry his respectable cousin. But on the eve of the wedding, Fleur and Twelfth Master Chan attempt to commit suicide together. In the 1980s, a young couple, Yuan and Chu, meet the ghost of Fleur and attempt to help her find Twelfth Master Chan, who never arrived in Hell with her. By the end of the film, it becomes clear that Fleur’s relationship with the Twelfth Master was more nuanced and disturbing than the audience originally understood. Ultimately, it is revealed that the Twelfth Master was resuscitated after he died and decided to keep living his life despite Fleur giving up her own for their love.

By the end of the film, it is clear that the past is not only different from how Yuan and Chu imagined it, but different from the way Fleur remembered it as well; the truth is that this romantic past never existed at all. True to Rey Chow’s primitive passions, Rouge comes to terms with nostalgia as a phenomenon that paints the past as more brilliant than it ever was. Unique to Rouge, the ghost of Fleur is able to function as both the symbol of the unattainable lost past and an entity with her own agency to change. Fleur’s duality means that she is able to legitimize the idea of nostalgia while realizing that it is not sustainable.

“Real things are always ugly.”—Rouge, 1988

While the plot functions on the premise of Yuan and Chu helping Fleur, this modern couple is able to understand their relationship through Fleur’s honest uncovering of the past. In the film, Chu wonders why her love for Yuan is not as strong as the love between Fleur and the Twelfth Master. Thus, an unattainable sense of nostalgia threatens her present relationship. However, because Fleur is able to interact with Chu in the present day and come to terms with her memory of Twelfth Master Chan being greater than he actually was, Chu realizes that her love with Yuan is, though not fantastical, real. In the film, Chu says, “Real things are always ugly.” But, she comes to realize that reality is more sustainable and reliable than grandized nostalgia. Through this realization, Rouge reveals that optimism for the future and contentedness for the present trump longing for the past when coping after trauma. From its inclusion of small jokes, such as Coca-Cola being a “foreign herbal tea,” to major themes, like an old theater turning into a 7-Eleven gas station, the film emphasizes the inevitability of change while unpacking the flawed lens of nostalgia. It becomes clear that nostalgia and love are forms of powerless, addictive intoxication that are dangerous for trying to view the world honestly and soberly.

As a film, Rouge acts as an interrogation of what Hong Kong’s future identity would look like. However, because film is a permanent and stagnant medium unlike theatrical performances, the film itself memorializes this period of transformation in Hong Kong. Rouge does more than work towards a future identity. In many ways, the film is the identity of the territory during this strange, liminal, and uncertain time.

Cultural Preservation in The Flower Princess

Tong Dik Sang’s The Flower Princess is one of Hong Kong’s most beloved Cantonese Operas, and it remains today one of the most reproduced Chinese Operas. The play is a hybrid of traditional Cantonese Opera and something new. The plot remains loyal to many elements of traditional Cantonese Opera, such as mistaken identity, chance encounters, doomed love, and a final wedding scene. However, the plot differs from traditional Cantonese Opera in its content between Han and non-Han powers and in its non-idealist ending (Lei). Rather than ending with a happily ever after wedding scene, Tong Dik Sang chooses to end the play with a double suicide carried out by Princess Cheungping and her lover.

The play centers around Princess Cheungping, the favorite daughter of the last emperor of the Ming Dynasty. The play begins with Cheungping meeting and falling in love with Jau Saihin, but things quickly turn chaotic when rebels attack the Dynasty. Cheungping’s father asks her and the other women in their family to sacrifice themselves to preserve their honor, but Cheungping is rescued from the palace before she can commit this act. The remainder of the play navigates through melancholy for the Ming Dynasty that is lost, defiance against the new dynasty, and attempts to salvage the love of Cheungping and Jau Saihin.

“Meeting again after the tragedy, it is as though we are living a new life.”—The Flower Princess, 1957

At the end of the play, Cheungping and Jau Saihin commit an act of loyalty to the past and defiance towards the future, but Tong Dik Sang nuances this romanticized nostalgia by making this act a double suicide. Rather than glancing at the past simplistically, The Flower Princess reveals that the struggle between individual desire and cultural expectations often leads to a bittersweet ending. Like Rouge, the play functions on a tension between the lost past and the overwhelmingly different present. After Saihin is reunited with the Princess after the fall of the Ming Dynasty, he says, “Meeting again after tragedy, it is as though we are living a new life.” This moment portrays post-trauma as disorienting and entirely disillusioning, emphasizing the need for one to re-start from scratch.

The Flower Princess was written in 1957 at a time when Hong Kongers were transitioning back under the control of the British after Japanese occupation ended in 1945 (Lei, 2014). Much like 1980s cinema grappling with the Handover, The Flower Princess works to understand both its imperial and colonial past without shallowly glorizing them. Audience members of the Opera often had one of two extreme reactions to the play: “either a sentimental longing for the good old days, or revulsion at the sappy cliché” (Lei, 2014). Like Rouge, The Flower Princess is a symbol of both optimism and longing, as a model for Hong Kong nationalism during the 1950s. The need to return to the imperial past of Cantonese Opera—a performance form meant to provide a set of “social and ethical mores meant to shape a cultural identity”—in order to re-situation Hong Kong a decade after this political shift emphasizes the long term effects of trauma on a territory (Lei, 2014).

Commercialization and Modernization of Nostalgia

Using traditional stories to look ahead is a creative way to work post-colonially, but there is a paradox in the commercialization of films like Rouge and the modernization of operas like The Flower Princess.

While Rouge goes against the popular anti-Handover film trend, it seems to have been marketed in a way that embraces Hong Kongers’ collective nostalgia. In the film’s trailer posted below, elements from the past, such as traditional theater makeup and Fleur’s flowery conservative dress, are placed next to one another in a way that shows the many literal and figurative ghosts lost over time in Hong Kong. These same imperialistic, nostalgic elements can also be seen in the video from the last act of The Flower Princess. The Rouge trailer focuses more heavily on Fleur and Twelfth Master Chan’s love story, only tossing in a few brief seconds of the supernatural elements that flood the film. The trailer seems to be more intent on marketing the film to capitalize on popular nostalgia culture than to reveal that its intent is to question this culture.

Similarly, The Flower Princess has been revived many times over the years to make it appear more accessible to modern audiences. In 2007, the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts modernized the production to incorporate spoken drama—a style imported from the West (Chan, 2017). While The Flower Princess’s form as an opera allows for fluid reimaginings and experiments, the need to modernize a production in order to interact with it seems to be of a colonialist mindset.

Performance as an art is not separable from colonial histories whose globalising effects have repeatedly demonstrated agendas meant to translate experiences for the benefit of the Western eye (Chan, 2017). Rouge and The Flower Princess exemplify this indivisible touch of the colonizer, even when nuancing and challenging nostalgia that makes the future seem daunting.

Conclusion

In both performances, time is manipulated to make the ideal “good ole days” seem recent and therefore more realistic. In The Flower Princess, the play begins post-fall of the Ming Dynasty. The audience is given a limited glimpse into the Dynasty, in which Cheungping finds love and all is well. In Rouge, Fleur returns to earth disoriented and unaware of the fifty years that have passed. The film relies on flashbacks that allow the thirties to feel like just as much of the present as the eighties to the audience. Fleur’s love story unravels slowly, allowing us to indulge in the fantasy of love before Fleur understands the sober reality of the past. However, the performances also undermine this recreation of nostalgia by incorporating unidealistic harsh truths. While Fleur is betrayed her lover after committing suicide and Princess Cheungping dies alongside her lover, both performances reveal that a too-firm grasp on the past can tragically shape the present. Fleur’s ghost began fading away the harder she looked for Twelfth Master Chan while Cheungping’s only way to go back to the things were was by killing herself.

Rouge and The Flower Princess emphasize Hong Kong’s need to return to the imperial past in order to rediscover, and therefore reinvent, Hong Kong’s identity. Both performances allow for contradictions in this method to come to the surface, rather than attempting to hide them. The works not only attempt to make sense of Hong Kong as a territory trapped between “first world imperialism” and “third world nationalism,” but act as documentations of the territory as a transitional nation (Chan & Willis, 2016).

Through rememory of an imagined past with art, Hong Kongers have been able to make sense of their post-colonial melancholy. This collective nostalgia has perhaps been the necessary ingredient needed to find nationalism in Hong Kong. While Rouge and The Flower Princess mourn for something lost, both productions are able to take this mourning and use it to collectively make sense of the present and reimagine the future. Hong Kong uses symbols of the past, whether real or imagined, as a foundation to build their identity of a transitioning nation stuck between being British and Chinese. The duality of stories that capture glimpses of the past but use forms that are able to be capitalistic and modernized show that Hong Kong will always be a hybrid of who it was in the pre and who it is in the post of colonization.

Bibliography

Chan, Felicia, and Andrew Willis. Chinese Cinemas: International Perspectives. London:

Routledge, 2016.

Chan, Felicia. Cosmopolitan Cinema. I.B. Tauris, 2017.

Lei, D. Alternative Chinese Opera in the Age of Globalization: Performing Zero. Place of

Publication Not Identified: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Leong, Anthony. “The Cultural Context of Rouge.” The Cultural Context of Rouge by Anthony

Leong, 1999, www.mediacircus.net/rouge.html.

Rouge. Directed by Stanley Kwan and Lillian Lee Pik Wah. Produced by Jackie Chan and

Leonard Ho. By Yau Tai Ping On. Performed by Anita Mui and Leslie Cheung. Hong

Kong: Golden Way Films, 1988. DVD.

Videos Works Cited

Cantonese Opera – Double Suicide from The Flower Princess. YouTube. September 24, 2015.

Accessed April 21, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mza5z-kWFwY.

Rouge (1988) Trailer. DionysusCinema. YouTube, YouTube, 5 Mar. 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=zEY41Gp0KOY.

Photography Works Cited

Figure 1: Dik Sang, Tong. “The Flower Princess: A Cantonese Opera.” MCLC Resource Center, Hong

Kong: Chinese University Press, 2010, u.osu.edu/mclc/book-reviews/flower-princess/.

Figure 2: “Yan Zhi Kuo.” Internet Movie Database, Golden Harvest Company, 1987,

www.imdb.com/title/tt0093258/mediaviewer/rm1761288960.

Figure 3: Kwan, Stanley. “Rouge – Yan Zhi Kou.” Film Society Lincoln Center, Golden Harvest Company,

Figure 4: Hong, Zou. “Law Kar-Ying (Left) Plays the Lead Role in the Cantonese Opera Three Dreams,

Which Was Recently Staged in Beijing.” China Daily, China Daily, 2015,

www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/2015-06/19/content_21048400.htm