Overview

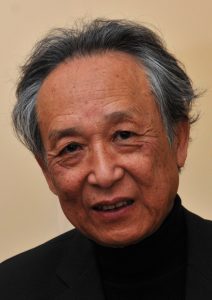

Nobel Prize winner Gao Xingjian left China to live on the outskirts of Paris and produced a stunning amount of high quality artistic work. In his play, The Other Shore, the playwright explores the difficulties and benefits of catalyzing individual identity. Global Theatre, in a narrow sense, consists of exploring plays reflective of religions, cultures and nations from around the world. The challenges and joys come from trying to understand theatre productions that draw from these many traditions. These areas where the lines dividing people become blurred offer an opportunity to examine theatre as it relates to the individual. To understand something as truly global, is to make it personal. This, in part, has to do with recognizing the common humanity every person the world over shares. Gao Xingjian’s play The Other Shore and the story of his own life’s journey are reflective of developing this individuality, the only universal human trait. The stated purpose of The Other Shore is to develop the theatre performer as a dynamic force made up of a multitude of parts in a single whole that remains connected to the rest of the world. Gao Xingjian and his work have much to teach use about how theatre is global to the individual.

Nobel Prize winner Gao Xingjian left China to live on the outskirts of Paris and produced a stunning amount of high quality artistic work. In his play, The Other Shore, the playwright explores the difficulties and benefits of catalyzing individual identity. Global Theatre, in a narrow sense, consists of exploring plays reflective of religions, cultures and nations from around the world. The challenges and joys come from trying to understand theatre productions that draw from these many traditions. These areas where the lines dividing people become blurred offer an opportunity to examine theatre as it relates to the individual. To understand something as truly global, is to make it personal. This, in part, has to do with recognizing the common humanity every person the world over shares. Gao Xingjian’s play The Other Shore and the story of his own life’s journey are reflective of developing this individuality, the only universal human trait. The stated purpose of The Other Shore is to develop the theatre performer as a dynamic force made up of a multitude of parts in a single whole that remains connected to the rest of the world. Gao Xingjian and his work have much to teach use about how theatre is global to the individual.

Biography

Gao Xingjian’s life as a writer helps illuminate how he came to write The Other Shore. The theme of individuality is perhaps the strongest motif of Gao’s writing and life. Gao was born during wartime China in 1940 and spent his first decades growing up under Mao’s Communist regime. Gao found himself heavily influenced by European absurdist theatre and literature in general, which led to his 1986 masterpiece The Other Shore. Gao was misdiagnosed with lung cancer late in 1986, this resulted in a ten-month trek along the Yangtze river during which he wrote Soul Mountain. By the end of the 1980s Gao had relocated to a town outside Paris, France where he produced a number of works critical of the Communist Party. After openly writing about the Tiananmen Square Massacre, all of Gao’s theatrical works were banned from performance in China. In 2000, Gao received the Nobel Prize for Literature and delivered a powerful lecture entitled, The Case for Literature.

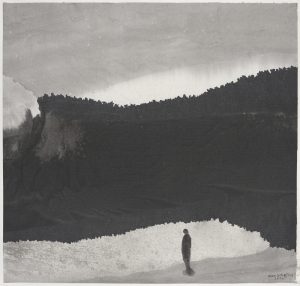

Gao has produced numerous artistic works over the course of his career including novels, screenplays, translations, paintings and plays. The theme of individuality runs through all of his works, like this watercolor painting titled Le Penseur which Gao recently did in 2016. “It can be said that talking to oneself is the starting point of literature and that using language to communicate is secondary. A person pours his feelings and thoughts into language that, written as words, becomes literature. At the time there is no thought of utility or that someday it might be published yet there is the compulsion to write because there is recompense and consolation in the pleasure of writing” (The Case for Literature).

Gao Sees writing, and art more generally, as an individual journey each artist undertakes by themselves for themselves. This painting captures the journey Geo describes, whose completion reveals the process of its production. Although I will be looking at Gao Xingjian and The Other Shore through the lens of individuality, I realize this is a lens that highlights certain elements of Gao’s work and not others. My motivation for this approach is based on his Nobel Prize Lecture on The Case for Literature. This lecture is the framework on which I examine The Other Shore. Also, I am taking the liberty of expanding the term literature to include artistic endeavors more generally.

The Other Shore

The struggle of the individual is captured in more than one scene from The Other Shore, one telling example is when Man encounters the Card Player. Here the game that is the performance is embodied inside another game, one that is rigged. They way that Man refuses to lie about what card is on the table has several meanings. When considered through the lens of the individual, many people see the event as a critique of the conformity of Mao’s Communist Party in China. I believe this reading is a bit shallow. “Literature is a universal observation on the dilemmas of human existence and nothing is taboo. Restrictions on literature are always externally imposed: politics, society, ethics and customs set out to tailor literature into decorations for their various frameworks… an aesthetic based on human emotions does not become outdated even with the perennial changing of fashions in literature and in art” (The Case for Literature). Although The Other Shore can be seen as a commentary on Communist China, Gao’s hope is that his work will outlast the times and serve as a call for individuality, “it is precisely for this reason that Greek tragedy and Shakespeare will never become outdated” (The Case for Literature).

The way Gao makes his theatre global is not by highlighting differences, rather he attempts to strip away the things that make us separate and focus on the experiences we all share. This is only possible from the perspective of an individual. The Other Shore can be seen as reflective of Gao’s own journey as an individual. Gao takes this journey and makes of it an exercise, one that is to be read and practiced. Although he draws from French and Chinese influences, The Other Shore is a play that anyone can perform. The transculturality of the play resonates with people approaching the play not as members of a race, religion or nation; but as an individual. In this way, Gao Xingjian is able to make his work truly global.

The Other Shore is a unique play because it is both a performance and a tool. At the end of the play’s text, Gao provides several suggestions on producing The Other Shore. “In order to free drama from its constraints and to revive drama in all its functions as a performing art, we have to provide training for a new breed of modern actors” (The Other Shore 42). The play was not written for a passive, witness-based audience in mind, “the present play is written with the intention of providing an all-around training for the actors” (The Other Shore 42). Gao places an emphasis on the play’s utility as a means of pushing performers to greater aesthetic heights. Even in the opening of the play Gao blurs the lines between performer and audience, “the play can be performed in a theatre, a living room, a rehearsal room, an empty storehouse, a gymnasium, the hall of a temple, a circus tent, or any empty space… the actors may be among the audience, or the audience may be among the actors. The two situations are the same and will not make any difference to the play” (The Other Shore 1). Gao wrote this play with functional, as well as aesthetic value in mind.

Gao takes this functionality a step further by literally opening the play with a game for the performers to play. The game of ropes emphasizes how the individual arises and is part of the world and owes his current condition to a great deal of arbitrariness. The rope game becomes more and more complex, flowering out into the loose narrative structure of the play itself. The play never clearly moves from the original game into the narrative of the play, so treating the entire play as a complex game for the actors is not unreasonable. This especially makes sense given the fact that Gao intended that the play be used as a teaching process for performers. And when I say performers, I think Gao would say individuals.

Final Thoughts

The faith Gao places in living as an individual is truly remarkable. I believe he puts it best himself, “literature transcends ideology, national boundaries and racial consciousness in the same way as the individual’s existence basically transcends this or that -ism. This is because man’s existential condition is superior to any theories or speculations about life. Literature is a universal observation on the dilemmas of human existence and nothing is taboo. Restrictions on literature are always externally imposed: politics, society, ethics and customs set out to tailor literature into decorations for their various frameworks” (The Case for Literature). To even approach theatre as a global phenomenon is to believe that the similarities of individuals can overcome group differences. That is what we all assume when we read plays and partake in performances thousands of years old from lands far away from our own. Gao has something to teach us about how we can connect and learn from others. The perspective of the individual is one that allows us to approach theatre as global.

Works Cited

Burckhardt, Olivier. “The Voice of One in the Wilderness.” PN Review, vol. 27, no. 2, 2001, pp. 28–32., www.obfuchai.com/pages/voice-gxj.html.

“Nobel Media AB.” Nobelprize.org, www.nobelprize.org/mediaplayer/index.php?id=138.

“The Other Shore.” YouTube, The Sons of Beckett Theatre Company, 21 Jan. 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=QV6RgjGscCA.

Xingjian, Gao. The Case for Literature. Yale University Press, 2006, books.google.com/books?id=WZ0ADCjp8XIC&pg=PA175&lpg=PA175&dq=The+Challenge+to+the+‘Official+Discourse’+in+Gao+Xingjian+early+fiction&source=bl&ots=6wsAqh8rpS&sig=Hl4tflaPqwJuP_8TKcUBjXtTLoE&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiv6LiU8KDaAhWqneAKHZKEC0cQ6AEIKjAA#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Yinde, Zhang. “Gao Xingjian: Fiction and Forbidden Memory.” China Perspectives, 1 June 2010, file:///C:/Users/arockwood/Downloads/chinaperspectives-5269.pdf.

Gao Xingjian – Nobel Lecture: The Case for Literature”. Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 20 Apr 2018. <http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/2000/gao-lecture-e.html>

Xingjian, Gao. Le Penseur. 2016, Galerie Claude Bernard, Paris, France.

Xingjian, Gao. The Other Shore: Plays. The Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, 1995.

Gao Xingjian. WikiMedia Commons, 14 Sept. 2012, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gao_Xingjian_(2012,_cropped).jpg.