Synopsis: The Soviet Union of the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s experienced heavy artistic censorship, despite its small strides in liberalism since Stalin’s death. Ballet was an art form woven tightly into Russia’s intra- and inter-cultural presence, and thus strictly monitored by the government. In rare cases, artists channeled ballet as an instrument of resistance, rather than propaganda.

Background

As the sun warms the earth, the spring in Russia is heralded by the sound of thick ice cracking.

Likewise, the era of Nikita Khrushchev — appropriately referred to as “The Thaw” (1955-1964) — began to crack the thick ice that had consolidated the USSR under Stalin’s regime of terror. Unfortunately, The Thaw failed to live up to the notions of liberalism its name conjured. Khrushchev was only able to condemn the actions of Stalin through his “Secret Speech,” the mass executions of previous decades were only acknowledged behind closed doors, nascent human rights groups only flourished underground, and the public still preferred novels to state-controlled newspapers as a source of information.

The newly-thawed Soviet Union failed to flow forcefully in any one direction. Thus, the the era of Brezhnev (1964-1982) would later be known as “The Era of Stagnation” — a period criticized for its political, economic, and cultural stagnation. Under Brezhnev, the arts became more accessible to the public, and artists were granted a greater range of experimentation. However, the state still only permitted art that it deemed consistent with socialist realism. Artists who repeatedly challenged the party narrative faced erasure, exile, or imprisonment.

Ballet is an art woven with particular emphasis into the Russian identity. Russia, frequently referred to as a crossroads of East and West, has throughout its history sought greater recognition from the West. In the 1700s, Russia adopted ballet as an access point to Europe — what it regarded as the cultural center of the world. In the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, Russia’s preoccupation with power and image had not changed. Touring Soviet ballet companies were carefully cultivated in order to convey a Russia that, under socialism, was prosperous, strong, and cultured. As figure 1 demonstrates, the USSR celebrated the international presence and cultural legitimacy it was afforded by ballet. Thus, control of prominent dancers, choreographers, companies, and ballets were considered a matter of national interest.

Despite overwhelming state pressure, a small number of artists publicly placed art before politics — often at great personal risk. This article examines individual artists and individual ballets as forms of resistance to the Soviet cultural project, and questions how such methods varied in efficacy.

Individual Artists

Resistance Through Defection

One blatant form of resistance was defection. The 1970s saw small wave of prominent Russian ballet dancers, both male and female, defect from the USSR. Typically, defection occurred when said dancer was touring outside of the country, and it rarely failed to make national headlines. The Soviet Union was aware that its dancers, particularly those in the international spotlight, posed a security risk. Thus, the KGB often applied preliminary coercion in order to prevent defection. Coercion did not persuade everyone, however.

Baryshnikov

It would be remiss to discuss famous defectors without mentioning Mikhail Baryshnikov. Baryshnikov is regarded as one of the greatest male ballet dancers of all time, and his name often appears alongside the likes of Nijinsky and Nureyev. In June of 1974, Baryshnikov defected to Canada while on tour there. Originally of the Kirov Ballet, he became a principal dancer of the American Ballet Theater. At the time, he described his defection as an act not of politics, but of art. A New York Times article from July 7, 1974 quoted him as saying, “What I have done is called a crime in Russia.… But my life is my art and I realized it would be a greater crime to destroy that.” While Baryshnikov may have chosen to emphasize artistry, his act had political ramifications. Soviet officials erased him from cultural discussion, and he never again returned to Russia.

The Panovs

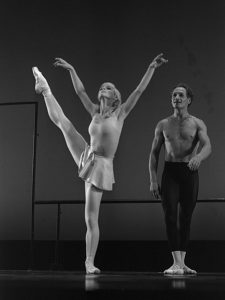

Valery and Galina Panov were the power couple of the Soviet ballet world. In 1971, they applied for exit visas to Israel, and their lives immediately imploded. Valery was banned from performance and arrested. Galina, a prima ballerina, was relegated to a member of the corps de ballet. Worse still, the KGB insisted Galina divorce Valery or end her career. In the end, the dynamic duo were saved by the outrage of the international community, and the government allowed them to emigrate to Israel in 1974. Figure 2 illustrates the happy continuance of their careers three years after emigrating. In a Chicago Tribune article from December 14, 1986, Valery is quoted as saying (of his persecution), “I was arrested, but I was already a prisoner. I was in a psychological prison.” The Panovs were able to escape the asphyxiating environment of propagandist art. Unfortunately, the political ramifications of their actions were mobile, too. In the same article — twelve whole years after their emigration — Valery lamented, “All the time, I have problems, political pressures from Russia….In Europe all theater belong to governments, to the state, to the political side. It all the time follow us. I think Galina is unlucky with me to be my partner.”

Bigger Picture

The 1970s saw the defection of not just the Panovs and Baryshnikov, but Rudolf Nureyev, Alexander Godunov, Natalia Makarova, Leonid Kozlov, Valentina Kozlova, and others. In terms of media coverage and cultural discourse, the exuberant voice of the West was typically juxtaposed by a silent Russia. Western accounts of the defectors were celebrated — and politicized — as a triumph of democracy, while Russian accounts were nonexistent. The below clip, for example, depicts To Dance, a musical stage adaptation of Valery Panov’s autobiography. To the West, Panov was not only a cultural icon, but a symbol of hope and liberty — and valuable evidence against the alleged ills of socialism. In one corner of the world, defectors were memorialized. In another, they were erased.

Resistance Through Remaining

Defection was not the only path of resistance to the oppressive conditions of the Soviet cultural project. The majority of artists did not defect. Of those who stayed, some found ways to rebel through ballet. Acts of balletic resistance within the USSR often failed to be as dramatic as, say, Baryshnikov’s headline-generating exit. However, instances of experimentation gradually tested ballet’s role as a political instrument of the state, and briefly returned it to the dancers. In an environment defined by the status quo, any deviation from the party narrative was artistic progress — no matter how small.

Maya Plisetskaya

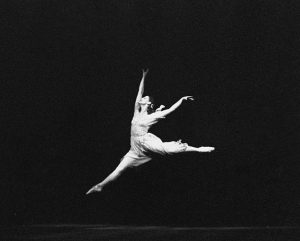

Khrushchev described Maya Plisetskaya as “not only the best ballerina in the Soviet Union, but the best in the world.” She was known for her gravity-defying leaps (see figure 3), touching musicality, and flexible back. Most captivating was her personality, which, at a time when purity and demurity were expected, shone through in a rush of passion and dynamism. It was this personality that propelled her through the “endless suffering and humiliation” that she later said plagued her memory. Plisetskaya born into a family that was Jewish on both sides. Additionally, under Stalin, her mother was sentenced to several years in a labor camp, and her father was killed in one of the purges of The Great Terror. Thus, not only had the Stalinist regime branded her an enemy of the people, but her religious and ethnic identity jeopardized her safety during a fresh wave of anti-Semitism in the USSR. Plisetskaya was banned from traveling until 1959, partly because the government feared she would defect. Her popularity eventually lifted the ban, and she became prima ballerina of the Bolshoi Ballet. She traveled abroad extensively and never defected. Plisetskaya was able to overcome the barriers erected by the Soviet Union in response to her family history. Moreover, she overcame such barriers on her own terms, through ballet that was progressive and exploratory.

Leonid Yakobson

Few figures were as controversial in the world of ballet as Jewish choreographer Leonid Yakobson. His work was deemed so earth-shattering that its effects were “like a bomb going off” — an explosion of identity and celebration made more impressive during a time when Jews were painfully suppressed. Yakobson creatively navigated the minefield of repressive state control, and produced work very different from its cultural backdrop. In a state that demanded conformist and didactic content, his ballets and choreographic miniatures explored individuality and daily existence. Contrary to orthodox Soviet ballet, Yakobson’s work favored contemporary music, turned-in and parallel foot positions, distorted and spasmodic movement, tilted lifts, eroticism, and psychological content. His career was repeatedly compromised by heavy censorship, job discrimination, and public outrage. The gravity of Yakobson’s resistance attracted prominent artists to his orbit. Plisetskaya, for example, famously danced in Yakobson’s Spartacus. Yakobson even created his 1969 ballet-miniature, Vestris, specifically for Baryshnikov. The clip below depicts Yakobson’s unusual utilization of pantomime, as well as his professional connection to Baryshnikov.

Bigger Picture

There was a formula for artists who rose to prominence in Soviet Russia: begin young, quickly ascend the ranks, attain a principal position, tour abroad, work as a ballet master, and perhaps open a school of dance. Artists who resisted totalitarian control and rose to prominence anyway were often uniquely gifted — thus, beloved by the international community, which was willing to interfere on their behalf. Once in a position of power, these dancers and choreographers had the opportunity to disseminate resistance through performing, teaching, and creating.

Individual Ballets

Spartacus

Spartacus is a ballet by the composer Aram Khachaturian. Ironically, its conception elevated Soviet ideology. Spartacus is the story of its title character, who led the famed Roman slave uprising from 74-71 BCE. Spartacus was lavishly praised in works by Marx and Lenin, and the Bolshevik Revolution granted him mythic hero status. The composition originated as a propaganda piece to boost Soviet morale during World War II, and its development was highly publicized. However, its premiere at the Kirov on December 27, 1956 was a different story. Yakobson was the first to choreograph and stage the ballet, and his artistic choices were so controversial that Spartacus was soon removed from the repertoire at the demand of a significant portion of the public. Yakobson staged the ballet off pointe and rejected tutus and traditional lifts. He focused on the psychology of each character, and placed struggle at the heart of his artistic message — not uprising. The grandiose movement was inspired by antique vases and sculptures. In the clip below, note the unconventional partnering, the emphasis on individual emotion, the two-dimensional movement, and of course, Maya Plisetskaya’s outstanding passion.

The Bedbug

The Bedbug was a play written by Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1928 as an acerbic critique of Communist society, later choreographed by Yakobson. The first part details the life of Ivan Prisypkin, who rejects his proletarian roots as he is literally and metaphorically seduced by the bourgeoisie. Through a series of unfortunate events, Prisypkin finds himself transported fifty years into the future to the Communist dystopia of 1979. In this world, sex, alcohol, romance, tobacco, dancing, and other pleasures are nonexistent. Prisypkin is imprisoned in a zoo, where he is exhibited alongside a bedbug, as both he and the bug are considered parasites. Yakobson combined sacrilegious content with a conception of Mayakovsky as the ballet’s hero, and free, grotesque movement as the artistic medium. Censors would not allow the 1962 ballet to be staged, and Yakobson was declared insane.

Bigger Picture

Yakobson was not the only resistant choreographer of the USSR. He was, however, one of the most powerful reminders that artistic boundaries could be pushed. At a time where ballet was a propagandist instrument, reshaping the conventions of dance sent a message to the dominant regime — regardless of whether or not resistant works ever reached the public eye. Movement had meaning, and even ambiguous political content was a small victory for experimenters.

Discussion Questions

- How does efficacy of resistance vary between artists who defected and artists who remained? From individual artists to individual ballets? Is there a spectrum of potency?

- This article did not have the means to address ballet companies as a third level of resistance (in addition to artists and ballets). How might a ballet company as an entity successfully stage resistant art? What are the dangers in being state sponsored?

- Some of the prominent artists discussed, like Valery Panov, Maya Plisetskaya, and Leonid Yakobson, were Jewish. Is there a connection between resistant art and ethnic minorities?

Works Cited

Text Citation

- “Baryshnikov, Defecting Dancer, Says Decision Was Not Political.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/07/07/archives/baryshnikov-defecting-dancer-says-decision-was-not-political.html. Accessed 19 April 2018.

- “The Brezhnev Era.” Russia: A Country Study, 1996. http://countrystudies.us/russia/. Accessed 18 April 2018.

- Clark, Kenneth R. “Freedom Gives The Panovs That Special Vitality.” Chicago Tribune. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1986-12-14/entertainment/8604030233_1_valery-panov-kirov-ballet-galina-panova. Accessed 20 April 2018.

- Ezrahi, Christina. Swans of the Kremlin: Ballet and Power in Soviet Russia. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

- Garafola, Lynn. “Maya Plisetskaya.” Jewish Women’s Archive. 1 March 2009. Updated in 2015. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/plisetskaya-maya. Accessed 20 April 2018.

- Romendik, Dmitriy. “Dancing their way to freedom: 4 great Soviet ballet defectors.” Russia Beyond. https://www.rbth.com/arts/2015/08/11/dancing_their_way_to_freedom_4_great_soviet_ballet_defectors_48425.html. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Ross, Janice. Like a Bomb Going Off: Leonid Yakobson and Ballet as Resistance in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press, 2015.

- Bush, Jason (reporter) and John Stonestreet (editor). “Maya Plisetskaya overcame terror legacy to redefine ballet.” Reuters. 3 May 2015. https://in.reuters.com/article/russia-ballet-plisetskaya/maya-plisetskaya-overcame-terror-legacy-to-redefine-ballet-idINKBN0NO0DQ20150503. Accessed 20 April 2018.

Media Citation

Images

- Figure 1: USSR Post. “USSR stampː Ballet Dancers.” 3 June 1969. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Soviet_Union_1969_CPA_3758_stamp_(Ballet_Dancers).png. Accessed 20 April 2018.

- Figure 2: Saar, Yaakov. “Galina and Valery Panov in the show.” 2 August 1977. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flickr_-_Government_Press_Office_(GPO)_-_Afternoon_of_a_Faun.jpg. Accessed 20 April 2018.

- Figure 3: Ozerskiy, Mikhail. “Maya Plisetskaya in Sergei Prokofyev’s Romeo and Juliet ballet.” 1 March 1961. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RIAN_archive_855342_Maya_Plisetskaya_in_Sergei_Prokofyev%27s_Romeo_and_Juliet_ballet.jpg. Accessed 20 April 2018.

Videos

- Video 1: “TO DANCE – A PASSIONATE NEW MUSICAL.” YouTube, uploaded by Tibor Zonai, 1 March 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iQcNWjMb7So.

- Video 2: “Baryshnikov and Yakobson, Vestris.” YouTube, uploaded by divannaru, 31 October 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lAX91L7xHHA.

- Video 3: “Leonid Yacobson – Spartacus.” YouTube, uploaded by Andreymozgovoi, 8 June 2008, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K6MY6wI36P0.